Poland is among the most immune countries to Russian disinformation and hybrid warfare. Our one-year long research focusing on Polish revisionist narratives has, however, revealed how the Kremlin is stoking bilateral tensions between Ukraine and Poland using historical tragedies or revisionism to exert influence. Since these narratives are first and foremost targeting nationalistic and extremist movements in Poland, it is essential to understand the drivers behind revisionist discourses to preserve the Euro-Atlantic Community’s unified stance against Russian aggression.

This article is a summary of a regional research covering the Kremlin’s and pro-Kremlin actors’ disinformation campaigns and active measures related to territorial revisionism in six countries – Poland, Slovakia, Ukraine, Hungary, Romania and Serbia – during a period of heightened nationalism and historical revisionism involving World War I commemorations between 1 January 2018 and 15 April 2020. The research, which utilised a novel methodology of qualitative narrative analysis combined with network and social media statistical approaches, presented us with a field manual on how to exploit historical conflicts, provoke extremist groups, and drive a wedge between two countries based on Russia’s disinformation campaign targeting Poland and Ukraine.

Bilateral relations between Kyiv and Warsaw have a long and difficult history. As neighboring countries, they were often opposed over border conflicts centering around the territory of Western Galicia and the city of Lviv, along eastern Poland and western Ukraine. While this territory was historically part of Poland for more than 300 years, several wars caused the region to switch hands and become a focus of the nation-state identity formation processes during the early 20th century. Lviv became one of the main Polish cities after Polish independence was regained in 1918 (and before). On the other hand, it is also home to a significant number of Ukrainian citizens, while it had also been a key city in Ukrainian plans for a reborn nation and eventually fell into the hands of then-Soviet Ukraine during WWI.

With such a conflicted and often bloody history in recent memory, it is no surprise that the Kremlin has identified the region as a critical wedge piece in its playbook for influence in Europe. So, what is at stake?

Russia’s ultimate goal is to create informational chaos in Poland and on a regional scale as well. Russian disinformation campaigns aim to polarize societies and countries, undermine trust in democratic institutions, and sow discord across Western Europe. In Putin’s ideal world, fabrications are indistinguishable from reality, history and propaganda are intertwined, and the public is oversaturated with noise. The Kremlin’s propaganda machine seeks to render the world unable to differentiate truth from lie, thereby enabling Russia to shape the informational narrative.

So how do influence operations operated by the Kremlin work based on our research?

One such tension point, as mentioned above, is the difficult border history between Poland and Ukraine. Bygone conflicts are still fresh in local memory, such as the war over Lviv in 1918 or the Volhynia Killings in 1943 - when Ukrainian troops (from the Ukrainian insurgent army) and citizens executed between 40,000 and 60,000 Polish civilians during World War II. This is a particularly sensitive topic for far-right and nationalistic groups from both countries, so it is an obvious base for a systematic disinformation campaign aiming to destabilize relations between Warsaw and Kyiv and polarize their societies.

Even though Poland is comparatively resilient to obvious Russian propaganda, there are still groups at risk to disinformation infection. Similar to Hungary for example, the far-right, nationalistic, and extremist movements in Poland have been target of anti-Ukrainian narratives disseminated on “independent”, “patriotic”, and pro-Kremlin websites. Interestingly, and also parallel to Hungary, almost all Polish far-right actors, parties, paramilitary movements, and media can be considered anti-NATO, anti-U.S., and anti-EU at the same time. What is even more relevant is that most are also anti-Russian, even though they are falling into the Kremlin’s geopolitical agenda. However, their ideology makes them vulnerable to anti-West messages and narratives on general if the sources of those communication cannot be traced back to the Kremlin or other pro-Kremlin actors. Kamil Basaj, founder and president of the INFO OPS Polska Foundation interviewed for our research identified three types of such sources: “patriotic,” “balanced” and “pro-Kremlin” portals presenting Russia either as a “powerhouse” or an actor of a legitimate great power “competition”

The Kremlin is no stranger to Europe’s informational environment. GRU officers and Russian operatives are capable of creating sophisticated and coherent disinformation campaigns utilizing suitable social media profiles, bots, and troll networks and especially closed groups on Facebook. Those groups bring together the target audience in one place, and without any supervision or control are the best tools of disinfo spread.

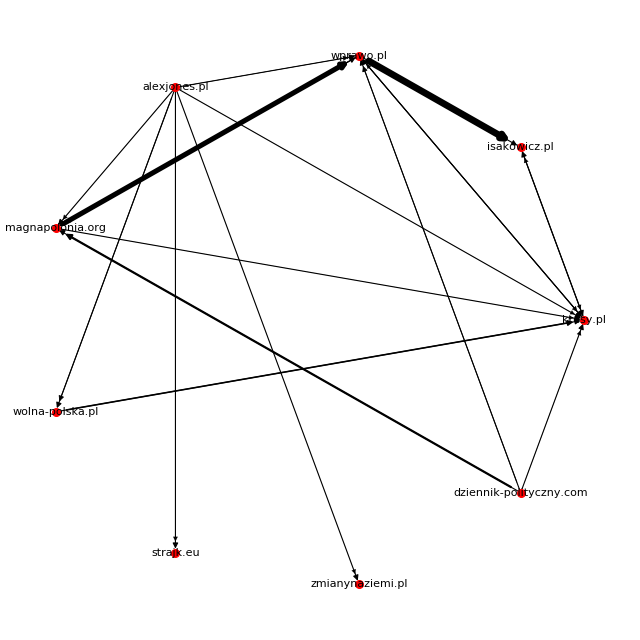

Once vulnerable groups are established on social media, they are easy prey for narrative insertion. In addition to social media, we also see a network of “freaky” portals who cross-post anti-Ukrainian narratives and weird conspiracy theories. In general, their job is to post politically-charged content tailored to specific audiences. Then the dissemination machine starts, where all donkey work is done by trolls by spreading the news, which contain the real venom and hateful narratives, which are important for the Kremlin. In Poland, fringe disinformation dissemination strategies not only utilize a distorted national identity rooted in revisionism against Ukraine and a dismissal of Polish membership in Western structures, but also employ a tight network of fringe Polish-language sites with strong connections to Polish far-right subculture. The network uncovered by our research is created using hyperlinks embedded into revisionist websites’ articles to direct audiences to similar narratives or legitimize their content through other, trusted third-party sites. As seen on the graph below, a tight Polish network of fringe sites is mostly organised around the central node of the Kresy.pl portal which cross-post contents through hyperlinks and act as a form of “echo-chamber” of pro-Kremlin revisionist narratives and coordinate disinformation activities.

To identify, map, and categorize the most prevalent revisionist narratives present in Poland, in cooperation with Open Information Partnership and Hungarian think-tank Political Capital, we took a random, representative sample of Polish website articles totaling almost 500. The recurring themes found within were categorized by narrative type, and their corresponding main messages, all relating to historical conflicts. We observed that the Kremlin is using those historical sentiments and conflicts over the region to fuel revisionist attitudes and stoke hostile sentiments in both Poland and Ukraine, against the Polish minority living in Ukraine (and vice versa). Putin’s propaganda machine is promoting these four main narratives and injecting them into far-right and fringe groups:

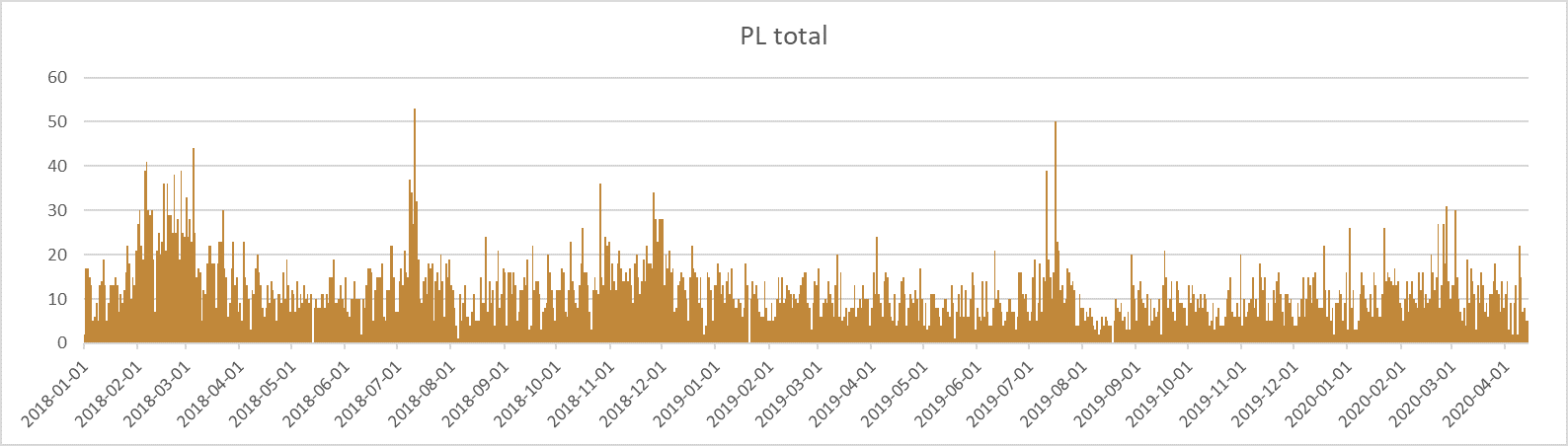

Our research found that Russia is using every opportunity to spread its toxic messaging. Over the analyzed period we saw that the rate of narrative injection and content generation increased during moments of tangentially related current events. For example, we observed a peak in fringe narratives posted on the Polish web during the Kerch Strait incident, as seen on the chart below.

Knowing Russia’s tendency to use hybrid conflicts, we can formulate a thesis that some of the events mentioned above were motivated or even executed by Russian Federation special services to shift attention of its attack on the Ukrainian navy in the Kerch Strait. In the Kremlin’s influence operations playbook, heating up territorial disputes, historical sentiments, and historical revisionism, form the basis of attacks towards Poland’s information space.

Now that everything is set up, you can just sit in your chair in the Kremlin and watch at the world catch fire.

So, what can be done?

As illuminated by our study, there are specific groups that are hyper vulnerable to malign operations. To improve Polish, but also Ukrainian, resilience, governments in Kyiv and Warsaw should establish a joint working group to tackle and counter-message the Kremlin’s campaigns targeting bilateral relations. The techniques and vulnerable groups are similar in both countries, therefore the most effective response would be a coordinated one. As the Kremlin aims to destabilize the region and alienate Ukraine from the West, creating a joint, international response group, would be a good message to send to Vladimir Putin.

This article is part of a series published about the research results of the project entitled “Revealing Russian disinformation networks and active measures fuelling secessionism and border revisionism in Central and Eastern Europe.” The research carried out in six countries – Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Ukraine, Romania and Serbia – between 1 January 2018 and 15 April 2020 was made possible by the generous support of the Open Information Partnership. For more, please visit the project’s website here.