Disinformation in the election campaign – Hungary 2022

Hungary has a uniquely disinformation-ridden media space. The disinformation narratives spread by the ruling party and the far right undeniably became dominant forces in the 2022 elections, especially as news and pro-Kremlin narratives about Russia’s recent invasion of Ukraine filled the media, overwriting earlier, economy-focused campaign messages. Fidesz took maximum advantage of its media dominance by using state resources, GONGOs, traditional and gray zone media to spread factually incorrect or otherwise misleading allegations and narratives about its political opponents, with virtually no external control. Pro-government media outlets also regularly provided safe-heavens for pro-Kremlin viewpoints, which usually reinforced Fidesz’s campaign messages.

Executive summary

- The disinformation narratives spread by the governing party and the far right have undeniably become a dominant presence in the 2022 Hungarian election campaign. The main focus was on discrediting opposition figures and especially opposition PM candidate Péter Márki-Zay. Naturally, Fidesz did not only actively attack the opposition candidate for prime minister, but also conducted a personalized smear campaign against individual candidates, based on a common narrative.

- The Russian-Ukrainian war has significantly altered the political discourse. Fidesz was forced to tailor its campaign to its divided voter base. While government communications and some articles in pro-government media condemned Russian aggression and focused on efforts to help those fleeing Ukraine, other reports in the state and pro-government media began to spread clearly pro-Kremlin disinformation narratives. Alongside economic issues, the key message became the fight of the "pro-peace right and pro-war left", similar to the narrative of the "anti-vax opposition" last year.

- The main disseminators of disinformation about the elections were the Hungarian state media, and traditional and gray-zone pro-government media organs. The state media had a traditional bias towards the ruling party, but the war made this particularly visible. A new feature of the campaign was that the vast majority of political messages disseminated on social media reached voters through gray-zone outlets.

- The main problem is the inaction of public authorities. The informal political control exercised by the ruling party over public authorities meant that they had no intention to act against the disinformation narratives being spread during the election campaign, leaving the fight against the phenomenon to the underfunded independent media and civil sector. The state's inaction thus left society completely vulnerable to political lies and war propaganda.

- In the next 1-2 years, support for the civil sector would help. Since in Hungary no meaningful action can be expected from state authorities to combat the spread of disinformation, it is worth turning to society. In many Eastern European countries, for example, civil initiatives have been launched to curb online trolling. It would be worthwhile to support similar civic organizations through training, recruitment, and networking. In the longer term, more active state intervention and stronger but balanced, regulation of social media would be an effective tool in the fight against disinformation.

Introduction

The disinformation narratives spread by the governing party and the far right have undeniably become a dominant presence in the 2022 Hungarian election campaign. Fidesz took maximum advantage of its media dominance to spread false and misleading allegations and narratives about its political opponents, with virtually no external control. Fidesz's information offensive has further worsened the already disinformation-ridden Hungarian media space, putting even more pressure on the remaining independent press. In this study, we investigated the disinformation and anti-democratic narratives circulating in Hungarian media in the two months leading up to the 3 April 2022 elections. The aim of the research was to map the disinformation used in the election campaign and the actors involved in its dissemination, as well as to document the strategies used in the campaign.

The formal electoral campaign was supposed to start only on 12 February, but the informal campaign had in fact started months earlier, and with it the dissemination of different narratives by political actors. This process was further intensified by the escalation of the Russian-Ukrainian war on 24 February, changing the focus of the campaign. For several weeks, the previous campaign messages, which had focused on economic issues, were completely replaced by narratives related to the war.

The outbreak of war forced the ruling party to condemn Russian aggression and to push its pro-Kremlin stance into the background. A differentiated campaign has been launched to bridge the gap between the government's previous pro-Russian foreign policy and its current communication. With Fidesz's voter base divided over the war, the ruling party's communications focused on peace and people's natural need for security to avoid losing voters. While government communications and some articles in pro-government media condemned Russian aggression and focused on efforts to help those fleeing Ukraine, other reports in the state and pro-government media began to spread clearly pro-Kremlin disinformation narratives. The latter narratives were mainly spread by 'experts', 'influencers' and lower-level pro-government politicians. The so-called gray-zone media, with a pro-government bias and anonymous or opaque ownership and editorial structures, expressed even harsher views.

The Our Homeland Movement and the far right have joined these 'efforts', linking their previous anti-Western conspiracy theories with pro-Kremlin disinformation narratives in their new campaign. They began campaigning against NATO and in favor of neutrality, somewhat in line with the Fidesz narrative and the broader anti-war sentiment generated by pro-Kremlin movements in the Central-Eastern European region.

In general, following the outbreak of the war, mainstream media[1] have (also) provided their readers with relatively objective, minute-by-minute information based on facts and figures. What distinguishes government-controlled media (public and private) from the critical and/or independent media is that they convey in opinion pieces positions that legitimize Russian aggression, Russian narratives used as a preconception for the invasion, and are explicitly hostile towards Ukraine.

It took a couple of days for the Fidesz media to find its focus again after the initial confusion after the outbreak of the war, which was a result of the fact that they had said for weeks before that Russia would never attack Ukraine, but after a controversial comment by Márki-Zay during an interview, in which he declared that “Hungary must implement the joint decision of NATO. So, if NATO decides to support Ukraine with weapons, of course [Hungary] will support it", they found the key message. The complete media space of Fidesz started accusing Péter Márki-Zay and the united opposition alliance of trying to drag Hungary into the war by wanting to send soldiers and weapons into Ukraine. It became the key message, refocusing the attention of the voter base on the “threat” posed by the opposition. The main message of Fidesz's campaign thus became "the pro-peace right and the pro-war left", similar to the anti-vaccine opposition's narrative last year.

The novelty of these campaigns was the extensive use of gray-zone media organs and campaigning within comment sections. Social media platforms, notably Facebook and YouTube, were flooded with targeted political ads, mostly in the form of short videos. Fidesz campaign messages were disseminated by sites such as the Megafon Center, Aktuális and Budapest Beszél, presumably consuming billions of Forints of taxpayers’ money. Like these large sites, dozens of smaller sites with a similar pro-government bias, anonymous or with opaque ownership and editorial structures, joined the campaign, diversifying the distribution of the governing party's positions. Perhaps the most notable example of these pages is the anonymous “Számok – a baloldali álhírek ellenszere” (Numbers - the antidote to left-wing fake news) Facebook page, whose posts mix the most common pro-Russian disinformation narratives with overt pro-Fidesz campaign messages. According to Telex's calculations, three quarters of the money spent on online political advertising poured into these gray-zone media outlets. While political parties are banned from accepting donations from foreign organizations, non-Hungarian legal persons, and anonymous donations, there is not law in Hungary regulating third party involvement in election campaigns.[2] Furthermore, regulation of political advertisement during an election campaign, has limited impact on platforms that are not officially linked to any parties or politicians. This is a way politicians and parties can easily circumvent campaign rules by outsourcing online campaigning to gray-zone outlets.

Fidesz has also used state resources to promote its own political agenda, blurring the line between party and state and between information and campaigning. The ruling party regularly uses state communication channels to spread its party political messages. Examples include the bias of the state media and campaign posters, where K-Monitor, Political Capital and Transparency International Hungary have highlighted irregularities in a report. Fidesz also spreads its message through the "NGOs" it controls, such as posters and advertisements commissioned by CÖF but financed by the taxpayer. Government agencies generally overlook the illegal nature of Fidesz's campaign, and the Constitutional Court regularly overturns court decisions that seek to punish disinformation.

Fidesz is thus able to widely disseminate messages and disinformation narratives that suit its political interests, both during elections and outside the official campaign period by abusing state resources, dominating the media and campaigning from the gray zone. The inaction of the state authorities gave the ruling party free rein to thematize the war, and the intensity of the spread of disinformation messages caught Hungarian society completely unprepared, presumably contributing to another two-thirds majority for Fidesz. There are many ways to combat disinformation, but as long as there is no political will on the part of the state to do so, or as long as the dissemination of disinformation is in the direct interest of the ruling party, the task will fall to the already struggling independent media and the civil sector. Support for civil initiatives to combat disinformation is therefore essential in the years ahead.

Key disinformation and anti-democratic narratives

Prior to the war (1 February – 23 February)

Before the escalation of the Russian-Ukrainian war, the ruling party's campaign was mainly focused on economic issues such as the utility cost cuts, the 13th month pension and tax rebates. The main message was that while the government was providing support to the population in the form of extra pensions, tax rebates, utility cost cuts, the opposition wants to raise taxes, re-introduce the hospital entry fee, privatize healthcare, take away utility price cuts and 13th month pension. One of Fidesz's most-watched videos in February sought to strengthen these claims. In addition, the Hungarian media gave considerable coverage to the government's so-called "child protection" referendum. The claims made in campaign messages were based almost entirely on half-sentences taken out of context or outright lies. The opposition coalition campaigned precisely on fixing state healthcare and the pension system, and Márki-Zay even fought many times against the parties to preserve the cuts in utility bills.

Péter Márki-Zay, the six-party opposition’s candidate for prime minister also campaigned on economic issues. He claimed that under the Orbán governments Hungary had become the "most corrupt and poorest nation" in the European Union. The prime ministerial candidate's claims were checked by Lakmusz, which found several instances of misrepresentations, but the extent of these was different in order of magnitude compared to the manipulative claims in the governing party’s campaign.

Another narrative was about former PM Ferenc Gyurcsány's[3] alleged leadership role, as a kind of puppet master, controlling Péter Márki-Zay and the opposition coalition. An example of this is the "Gyurcsány show" campaign, which often appeared in advertisements and on posters, in which the leader of the opposition coalition is portrayed as Ferenc Gyurcsány's man, thus simplifying the political contest into a two-man duel between Viktor Orbán and Ferenc Gyurcsány. The campaign itself was launched before the opposition primaries and was always refitted to the candidate who was winning at the time - first Gergely Karácsony, lord mayor of Budapest, and then Péter Márki-Zay.

Two political parties, Our Homeland (Mi Hazánk) and Normal Life Party (Normális Élet Pártja, NÉP), campaigned with medical disinformation narratives and conspiracy theories regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. The latter wrote in its manifesto that in their belief:

- The SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus is most likely man-made and spread from the laboratory in Wuhan, China.

- The US and Chinese governments are equally responsible for the development of the virus.

- The outbreak has been artificially inflated along a long preparatory process, the main drivers of which are the pharmaceutical and hospital industries, Big Tech companies, partly as direct investors in the pharmaceutical and hospital industries, and partly as investors seeking to gain business opportunities and expand their influence through the collection of personal data. Software maker Bill Gates, Anthony Fauci, the US President's chief adviser on epidemiology, and Tedros A. Gebreijus, the WHO President, have played and continue to play a lion's share in the implementation of the organization.

After the start of the invasion (24 February – 31 March)

For a couple of days, the war completely dominated the media space, and it took the pro-government media some time to recalibrate its narratives. A differentiated campaign started to smooth differences between the government’s previous pro-Russian foreign policy and its current communication. With Fidesz's voter base divided over the war, Fidesz had to communicate different messages at the same time to avoid dividing their own camp and giving the pro-Kremlin communication space to a political opponent - primarily Mi Hazánk. These messages were contradictory to say the least, as the government's official statement condemned Russia's aggression, while anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western opinions portraying Russia as a victim were reinforced in the pro-government media. The subsequent "peace communication" – focusing on “neutrality” and the need for peace and security instead of “taking sides” - also proved effective because it was able to appeal not only to Fidesz voters, but also to opposition ones. It portrayed Orbán as a competent statemen, who can protect the interests of the Hungarian people, thus projecting stability and leadership, despite its flip-flopping foreign policy stance on Russia.

On the other hand, as a counter-measure, the complete media empire of Fidesz started accusing Péter Márki-Zay and the united opposition alliance of trying to drag Hungary into the war by sending soldiers and weapons into Ukraine. It became the key message, refocusing the attention of the voter base on the “threat” posed by the opposition. The main message of Fidesz's campaign thus became "the pro-peace right and the pro-war left", similar to the anti-vaccine opposition's narrative last year.

- The Left would send weapons and soldiers to Ukraine, thus dragging Hungary into war

- Based on Péter Márki-Zay's previously mentioned half-sentence, the pro-government press, and later the entire pro-government political elite began accusing the opposition of wanting to send Hungarian soldiers to Ukraine immediately, "dragging" Hungary into war. "The government supports Ukraine's sovereignty, and our country is also in line with the common EU position. In contrast, the left is using the current situation for campaigning. And Péter Márki-Zay would send Hungarian soldiers and weapons straight to Ukraine." - wrote Magyar Nemzet.

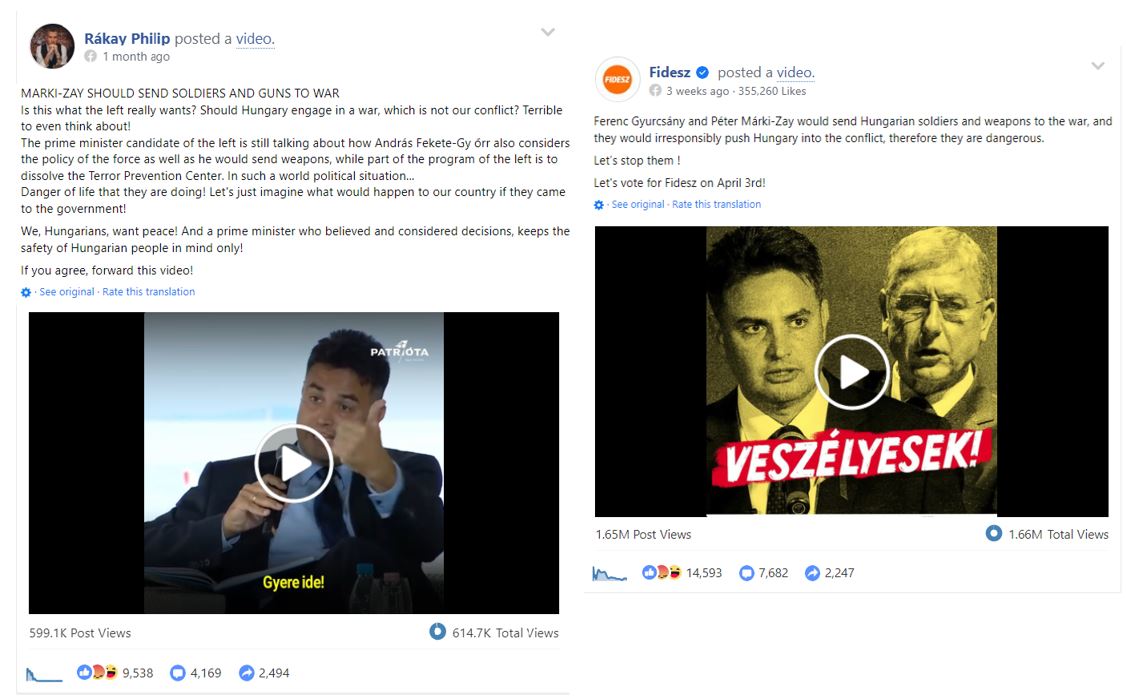

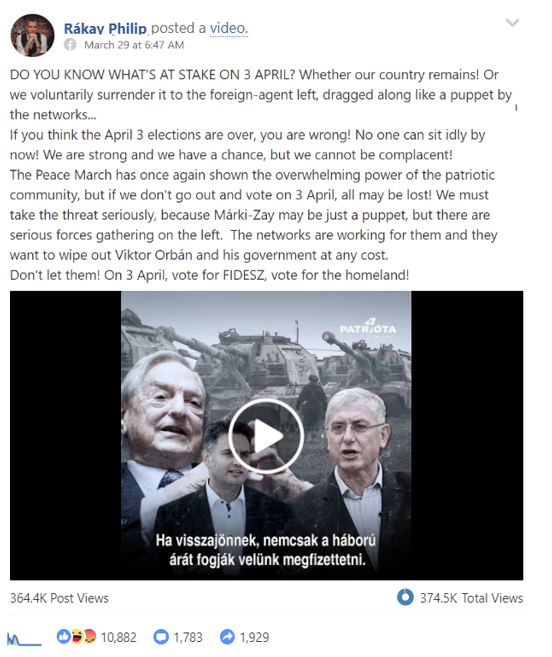

Philip Rákay, a pro-government influencer's post, repeating Fidesz's campaign messages

- The left would abolish the utility cost cuts.

- Another key message was still focusing on economic narratives previously mentioned, but reinforced by the war narrative, claiming that by dragging Hungary into the conflict the opposition would destroy the government’s achievement such as the utility cost cuts. "Not only did they not vote for our measures, but they kept attacking them. The best example is the utility cost cuts. If somebody cuts off Russian gas and oil, which they are about to do, how are they going to defend the cuts? That's impossible." - Viktor Orbán said in an interview.

- Foreign forces are interfering in the election in support of the left

- The latest element in the narrative was the claim that the opposition had allegedly agreed with international actors, such as Ukraine, to immediately start arms deliveries to Ukraine and to vote for sanctions on gas and oil supplies in the event of their election victory. Here, several narratives ('foreign agent', 'pro-war left', 'abolition of cuts') merged in the last days of the campaign.

- Left = War, Fidesz = Peace

- Fidesz's position may have been strengthened by the fear of war, and it seems that after a short period of uncertainty, Viktor Orbán incorporated people's need for security and stability into his campaign more effectively than the opposition. Accordingly, Fidesz's campaign focused on repeating the message. – “War or peace. If we want peace, we should choose the national side; if you want war, support the left."

On the government side, the current situation increasingly seems to be that there is a 'central', largely pro-Ukraine narrative from the political elite, that objective reporting is present in the pro-government media, while the transmission of pro-Kremlin, anti-Ukraine narratives is 'outsourced' to experts and opinion leaders grouped around Fidesz - and then these opinions and analyses appear in the columns of the government-controlled press.

At the same time different pro-government media sites started to spread pro-Kremlin disinformation narratives about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, sometimes directly borrowing from the Kremlin’s playbook. This is mainly spread by commentaries and through invited experts in the state media, while the reporting on the news remains neutral.

The government-controlled media justified the Russian invasion with the following Russian strategic narratives:

- The Russian minority in Ukraine must be protected from atrocities or alleged genocide:

- On the main state channel M1, the senior foreign affairs editor of the public media explained that Putin is acting to protect the Russian-majority population of Donetsk and Luhansk provinces.

- A foreign affairs expert also justified the Russian operations on M1 by saying that "whether genocide in the classical sense of the word has taken place is not known" (while the Russian side has no evidence to support this either).

- A legal expert from Századvég stressed on the M1 news channel that Vladimir Putin is referring to genocide by Ukrainians and that nuclear weapons are being developed in Ukraine. "If these allegations are correct, they would cloud the picture of unilateral war", the expert added[1]

- It is NATO or Ukraine's aggression that is responsible for the conflict:

- A security policy expert at the Centre for Fundamental Rights told M1 that the United States was "working hard" to "disengage" Ukraine from Russia, and that it was unacceptable for Vladimir Putin.[2]

- György Nógrádi, one of the best-known post-Soviet experts, now a pro-government expert, says it is in Russia's interest to have a Ukrainian leadership that does not want nuclear weapons.[3]

- Ukraine as a state does not exist or is an artificial entity:

- "I can tell you frankly, I am completely unconcerned about what will happen to the Ukrainians. (...) And no, I'm not fucking moved by the situation in Crimea, for example. (...) Who has more rights to Transylvania, us or the Romanians? And yet Transylvania has been under Romanian rule for twice as long as Crimea has been under Ukrainian rule", one author of Pesti Srácok explained.

This content is much more likely to be shared on social media. The reach of pro-Russian messages has been boosted significantly by, for example, the trolling activity on Facebook in recent years. The artificially induced reach is mostly achieved by trolls through repeated comments, as Facebook's content recommendation algorithm explicitly rewards "meaningful social interactions"; i.e., comments. Facebook has not yet take steps to mitigate the effects of this technique. Since there is only one known Hungarian Facebook fact-checker working for news agency AFP, the capacity of such fact-checking activities is also limited.

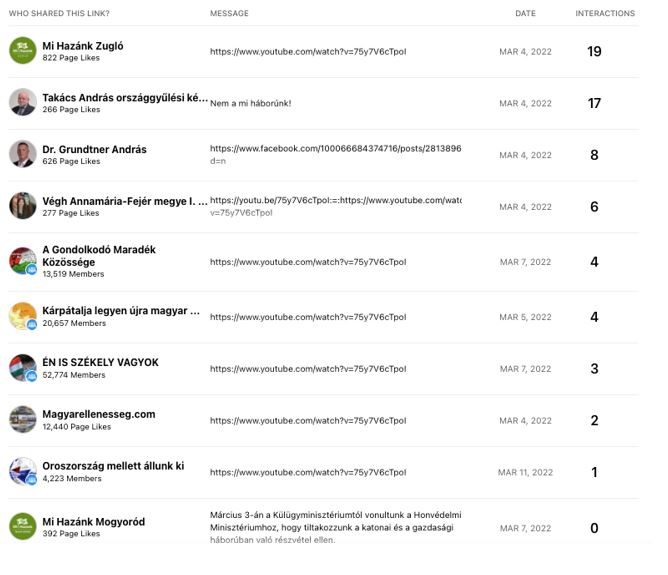

Our Homeland Movement joined these “efforts” and connected their previous anti-West conspiracy theories to pro-Kremlin disinformation narratives in their new campaign. Lately, the representatives of this political party started campaigning against NATO, and in favor of neutrality, somewhat in line with Fidesz’s narrative and the larger anti-war sentiment generated by pro-Kremlin movements in the CEE region.

- For example, according to László Toroczkai, PM-candidate of the party, the "foreign-led revolution and coup" of Euromaidan itself was not legitimate, because the corrupt Yanukovych was followed by an equally corrupt leadership. Ukraine is also blamed for its rapprochement with NATO and the EU and for its arms build-up, which allegedly flouts the Budapest Agreement. The video shared by László Toroczkai was further shared by Facebook groups and pages of various politicians and public groups including Kárpátalja legyen újra Magyar… (Make Transcarpathia Hungarian Again…), Anti-Hungarianness.com, Oroszország mellett állunk ki (We stand by Russia). See full list below.

- Toroczkai also echoes the Kremlin's narrative that bio-weapons laboratories were set up in Ukraine with the Pentagon’s support.

- Toroczkai also cited the alleged genocide in Donbass, which has not even been substantiated by the Kremlin, and the OSCE mission monitoring the conflict on the ground has found no evidence of it.

- Our Homeland has launched a petition on its website to stop the government from supporting sanctions that would harm the Hungarian people and called on the government "not to make Hungarians pay the price of the US-Russian war, subserviently fulfilling the demands of Brussels and NATO".

- According to Mi Hazánk, one of Hungary's interests is to stay out of the war, and they therefore reject the transfer of armed forces to Ukraine, as well as the arrival of US or other Western troops in Hungary "to prepare for a possible attack". Moreover, Toroczkai said, it is important for Hungarians to open the eyes of their allies, so that European nations do not allow themselves to be dragged into a war aimed precisely at weakening Europe.

- Gyula Popély, the party's candidate for president, said that the territorial integrity of the Ukrainian state was not in any Hungarian national interest.

- During the last week of the election campaign Facebook took down the page of political party Our Homeland (Mi Hazánk) for allegedly violating the community guidelines without specifying what was the violation.

Along with other international anti-vax movements, the Hungarian anti-vax community also started to spread pro-Kremlin narratives. The Normal Life Party, established by a popular anti-vax leader György Gődény, released a statement, where they repeated pro-Kremlin disinformation narratives about the war. They encouraged the Ukrainian government to “stop the military actions against the Russian population in Ukraine, which was one of the causes of the conflict”. They also “understand the Russian side's concern about Ukraine's accession to NATO and we condemn the fact that the Atlantic bloc is further provoking Russia by expanding and deploying more and more weapons systems.”

The effects of these disinformation campaigns are starting to show:

- According to a recent opinion poll by Medián: 43% of Fidesz voters think that “Russia has acted legitimately to protect its interests and security” when it attacked Ukraine last in February, while only 37% viewed that “Russia has committed serious and unjustified aggression against Ukraine” and 20% remained undecided.

- Contrary to that, only 9% of the opposition voters think that “Russia has acted legitimately to protect its interests and security” when it attacked Ukraine last in February, while 84% viewed that “Russia has committed serious and unjustified aggression against Ukraine” and 7% remained undecided.

- Those who supported “other parties” were divided too: 38% of them thought that “Russia has acted legitimately to protect its interests and security” when it attacked Ukraine last in February, while 50% viewed that “Russia has committed serious and unjustified aggression against Ukraine” and 12% remained undecided.

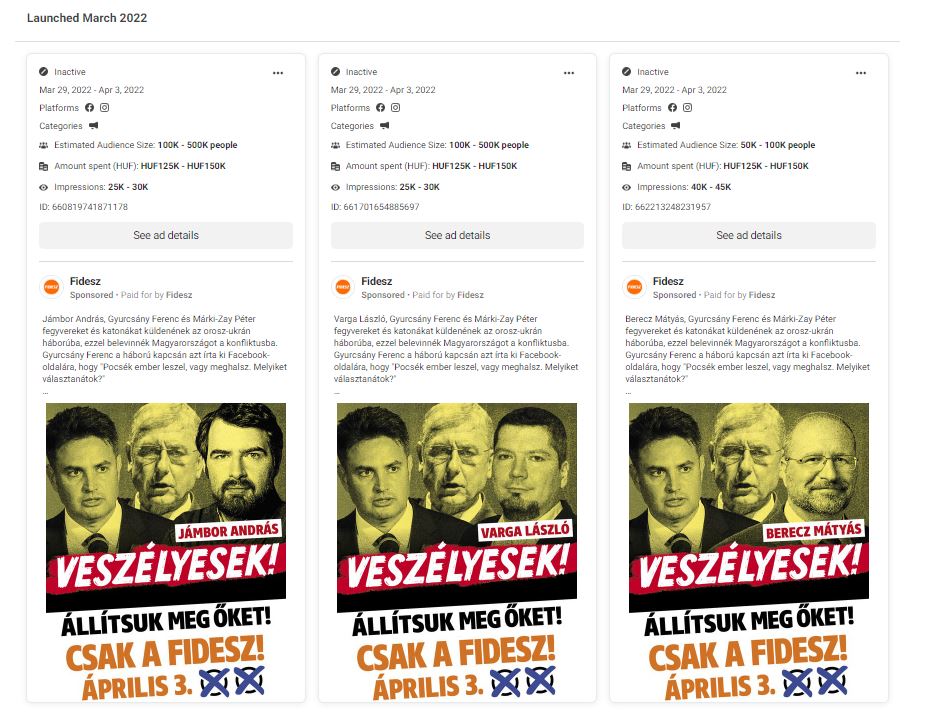

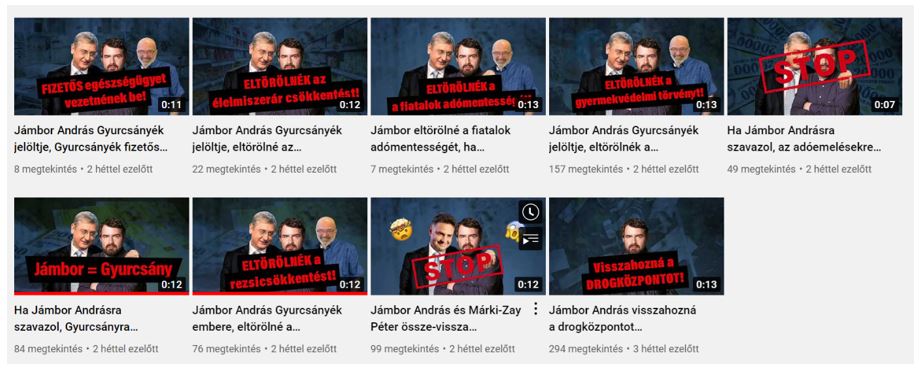

Attacking local candidates from the gray zone

Of course, Fidesz did not only actively attack the opposition candidate for prime minister, but also conducted a personalized smear campaigns against the individual candidates, with a common theme mentioned above. They were generally accused of being “Gyurcsány’s man”, campaigning for war and wanting to abolish utility cost cuts. Telex identified campaign machinery and gray-zone smear sites with similar themes and strategies in 42 single member constituencies (SMC) out of the 106. Such campaigns were also launched against opposition candidates András Jámbor (Budapest 6th SMC) and Tímea Szabó (Budapest 10th SMC), among others.

Facebook ads by Fidesz, spreading the same disinformation narrative about different opposition MP-candidates connecting them to PM-candidate Márki-Zay, and former PM Ferenc Gyurcsány; Source: Facebook Ad Library

András Jámbor was accused of, among other things, abolishing the utility price cuts and turning the district into a drug farm by the media around Fidesz via an extensive online and offline campaign material. The strategy is similar to the smear campaign against Péter Márki-Zay: a half-sentence from a speech or interview is distorted and used to build a campaign message.

A selection of videos from the YouTube channel "Not Jámbor", created to discredit András Jámbor

Tímea Szabó, a traditional target of many attacks and smear campaigns, was accused of being a CIA agent, or more recently of allegedly financing her campaign through cocaine trafficking. What is interesting about these accusations is the technique with which they are being spread. The accusation is presented in a video by a man impersonating a member of the Anonymous hacking group, which is being adopted by the pro-government media as clear evidence. There was a similar smear campaign in the City Hall case, where footage and various allegations were published in the press that the Gergely Karácsony administration wanted to sell the Budapest City Hall building. However, the investigative committee of the Budapest Assembly set up to look into the case found no evidence of this. It has to be mentioned here that the committee was dominated by opposition politicians. Nonetheless the independent media is also highly doubtful about the claims of this “Anonymous” figure.

Who are the crucial disseminators of election-related disinformation?

The state and pro-government media

The public service media has been criticized for years for being heavily politicized and favoring the narratives of the government and failing to comply with professional standards. However, when a war started in a neighboring country, the biased nature of the public service media in Hungary became more obvious.

Russia has been using state financed propaganda to disseminate disinformation worldwide. Despite the restrictive measures put in place by the European Union targeting Russia Today and Sputnik, Russian war propaganda has been continuously disseminated in Hungary. Nonetheless, Hungarian public media channels continue to use Russian propaganda as a source, and at other times broadcast disinformation messages from Russian officials such as Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov or spokesman Dmitry Peskov without criticism, thus inadvertently spreading Kremlin propaganda. It should be added, of course, that this is also sometimes done by the independent media, too.

The Hungarian authorities enable the dissemination of Russian war-propaganda by not sanctioning the public service media in cases when it presents disinformation as truth. Although in some cases the public service media used a sophisticated method, as its programs did not directly share reporting by sanctioned media outlets, it still disseminated the same notions and ideas that serve the Russian narrative without providing context or countering arguments. In other cases, the sanctioned Russian sources were directly quoted.

The disinformation is also echoed by the pro-government newspapers of Mediaworks Group and KESMA. Because the ruling party has influence over the overwhelming majority of the Hungarian media, it is able to shut out alternative interpretations, including those of opposition figures, from a significant part of the Hungarian population. With few exceptions, the voices of opposition figures have been relegated to the remaining independent media outlets and the smaller opposition media of the major opposition parties over the last decade. And the domination of the Hungarian media space has created a nationwide echo chamber, where the ruling party has asymmetric access to media space.

Our Homeland and the far right

The majority of far-right actors in Hungary evaluate the Russian aggression against Ukraine according to their well-established thought patterns and argumentation. Their explanations typically reflect conspiracy theories based on anti-liberalism, anti-Westernism and especially anti-Americanism, a sense of satisfaction for the grievances of the Transcarpathian Hungarians, uncritical receptivity to the Kremlin narrative, and an exclusive nationalist definition of national interests, but they also filter through racism and anti-Semitism. The most active players on the issue are the Our Homeland Movement, the Hatvannégy Vármegye Youth Movement and Ábel Bódi, a leader of the Identity Generation, but also Edda Budaházy, the Betyársereg, the Hungarian Self-Defence Movement and Tamás Gaudi-Nagy, head of the National Legal Defence Service, have expressed their views. The following main narratives emerge from their speeches:

- Ukraine deserved the Russian attack.

- Russia acted legitimately, in response to a threat.

- The US is mainly responsible for the war, it serves its interests.

- The Russian troops are trying to behave humanely, but the Ukrainians are committing war crimes.

- The West is applying double standards in its condemnation of Russia.

- Hungary should stay out of the war and not (so much) concern itself with Ukraine's territorial integrity.

- In contrast to the migrants coming in 2015, the 'real refugees' from Ukraine must be helped, who are primarily Hungarians from Transcarpathia.

Strategies and methods used to spread disinformation

The misuse of public resources

Fidesz is regularly using state resources – and taxpayers’ money – to further its own political agenda, blurring the line between party and state, and between providing information and campaigning. The ruling party uses the communication channels of the state to distribute its partisan political messages.

The government’s narratives are sometimes communicated via the so-called “coronavirus newsletter”. Only a couple of days before the election, citizens registered on the mailing list of the Government Information Centre (GIC) for the coronavirus vaccination, found a letter in their inbox asking them to vote no in the national referendum on the third of April.

Another example is the case of the campaign posters. According to a report by K-Monitor, Political Capital and Transparency International Hungary, a poster campaign worth more than HUF 3 billion was launched in March to support the governing party.

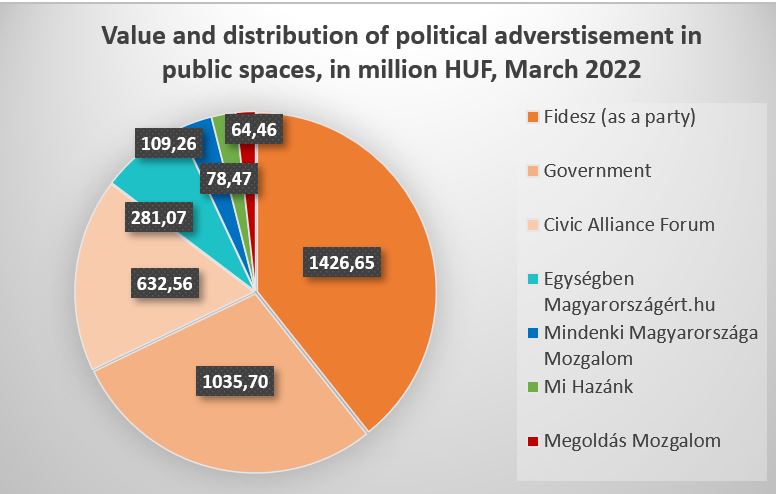

- The Fidesz-organized NGO called the Civic Alliance Forum (CÖF) and the ruling party, supported by the Cabinet Office of the Prime Minister, commissioned advertisements on 12 171 billboards worth more than HUF 3 billion at list price only in March. Together they spent eight times more than the opposition and three time more than the legal limit. Fidesz, as a party, spent about HUF 1.4 billion, the government 1 billion and the CÖF spent more than 630 million, so the ruling party in itself overspent the limit of 1,17 billion for all campaign advertising costs.

- In contrast, the opposition led by Márki-Zay had only 1564 billboards at a much lower cost of HUF 390 million.

Value and distribution of political adverstisement on public space, in million Ft, March 2022; Data source: Outdoor Media Kft, collected by K-monitor

State agencies usually overlook the law-breaking nature of the Fidesz campaign. The State Audit Office and the Media Council should immediately take action and stop Fidesz’s and the government’s illegal campaign activities, but they have long ceased fulfilling their functions as independent watchdogs. The same is true for the Constitutional Court, which routinely overturns the rulings of lower courts that sanction disseminators of fake news and targeted political disinformation, and lets disinformation be spread uncontrollably during elections. The decisions of the Constitutional Court are fully in line with the political interests of the ruling party.

The main problem is not necessarily the inadequacy of legislation, but the informal exercise of power over state bodies. The state apparatus and the security services could effectively combat disinformation in the Hungarian media space even without a major change in the law, but the lack of political will is hampering any efforts to do so. Leaders loyal to Fidesz at the head of "independent" state institutions regularly interpret the law in the party's interests. An excellent example is the Media Council, which is composed exclusively of Fidesz-appointed officials and regularly decides controversial issues in line with the interests of Fidesz. If the ruling party - against its own interests, of course - would allow the state to enforce the laws in force and use its resources on a professional rather than a political basis, action could, theoretically, be taken against the phenomenon. This is, however, unlikely to happen in the foreseeable future in the current political environment, given that one of the most significant purveyors of disinformation narratives is the state media itself and the biggest beneficiary is the ruling party.

Operating in the gray zone

The novelty of this year’s electoral campaign campaigns was the extensive use of gray-zone media organs and campaigning within comment sections. Social media platforms, notably Facebook and YouTube, were flooded with targeted political ads, mostly in the form of short videos, almost without any interference from the platforms. Telex calculates that more than three times as much advertising money flowed into the gray zone on Facebook than into the official campaign spending sites. In the 50 days of the official campaign (between 12 February and 3 April), political actors spent more than HUF 3 billion on Facebook ads alone. A significant proportion of this - 80 percent of the funds for Fidesz and 65 percent for the opposition - went to the gray zone. 444.hu has also regularly investigated advertising money spent on online platforms, and their investigation came to similar conclusions.

Fidesz campaign messages were disseminated by sites such as Megafon Center, Aktuális and Budapest Beszél, presumably consuming billions of forints of taxpayers’ money. Like these large sites, dozens of smaller sites with a similar pro-government bias, anonymous or with opaque ownership and editorial structures, joined the campaign, diversifying the distribution of the governing party's positions. On the opposition side, there are also such informal channels to convey political messages. The most prominent of these is the Ezalényeg network, which consists of roughly 80 sites, including Ezalényeg, Ez van, Vélemény Klub, Röviden.info, Pegazusinfo, Covidoltás.info, Lényeglátók, Nerpédia and Erősítő.

It is worth noting here that, as in the Hungarian media space in general, the opposition did not start on equal terms. In the 50 days of the official campaign period, the media that broadcast Fidesz messages spent HUF 1.46 billion in this way, while the political players behind the sites presumably spent HUF 663 million on advertising the opposition's messages.

This provides a clear overview of how the campaign messages of the ruling party is being spread. Using state resources, GONGOs, traditional and gray zone media, Fidesz can vastly overspend the opposition in the media space, both offline and online, on traditional and social media.

Campaigning in the comment section

One of our recent study looked at recurring posts on Facebook regarding domestic policy issues. To do so, we looked for comments that are copied hundreds of times, essentially textually identical, by users under posts or in response to others' comments, thus spreading the narrative. For our analysis, we collected all comments between 1 September 2021 and 15 January 2022 that contained the words Orbán, Fidesz, Gyurcsány, or Márki-Zay. The narratives that emerged included both pro- and anti-government narratives, so it can be said that both sides used this method. The topic of the four repetitive comments examined was as follows:

- Harmful consequences of the opposition takeover (pro-government)

- 100 questions by Tímea Szabó (opposition)

- Zsolt Gréczy's pamphlet against "Gyurcsányisation" (opposition)

- a list of the sins of the Medgyessy, Gyurcsány and Bajnai governments (pro-government)

Based on the analysis of the profiles that disseminate the narratives, we were able to distinguish three main groups:

- Diligent activists pass on the narrative only a few times, and then only in a narrow time frame.

- The leader activists spread the narrative over a long period of time. But it can be months between two occasions, and their activation can be observed when the dissemination of a given narrative by hard-working activists ends or a new intensive campaign is launched.

- A professional troll is a person who disseminates narratives very intensively (for long periods of time, without any meaningful breaks, several times a day). His activity is typically concentrated during working hours, which indicates that his activity is work-related.

As mentioned in our previous analysis, the dumping of repetitive narratives in Facebook posts is obviously beneficial to the political actor who is favored by a given narrative. If it happens completely organically, it does not even cost resources. And with coordination, even more effective results can be achieved. All three profile groups listed above can be said to be engaged in a different – inauthentic activity than the average Facebook poster.

Repetitive commenting degrades the quality of the exchange of ideas under Facebook posts. It creates tension between those with differing views, "bashing" each other is often observed in an environment of repetitive narratives. In the ensuing debate, tribal logic is reinforced and negative adjectives are used. Profiles that do not display public information reduce trust. This in turn diverts users who are open to normal debate. In turn, the amplification of the narrative presents a distorted picture of what the majority opinion is.

Another consequence of party-coordinated narrative propagation is that it is not transparent to say the least. While ad spending on political issues has been public on Facebook since 2019, allowing us to see the huge amounts of money those political organizations spend on such causes, the narratives spread through comments are very difficult to observe. Due to data protection restrictions, little information is available about the distributors. Thus, we do not know how real and serious is the often-mentioned troll army in Hungary. Based on our previous case studies, we can certainly talk about activists and professional trolls. However, we do not know the organizational and operational background behind them.

Facebook previously started reporting their countermeasures against these types of coordinated inauthentic behavior (CIB) but looking through their reports, it seems that these cases are essentially ‘flying under their radar’. Especially in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Meta is mostly paying attention to misinformation and trolling done by Russia.

Case studies

As previously mentioned, one of the key narratives of Fidesz was the opposition would allegedly send Hungarian soldiers to Ukraine. This message was broadcasted on every available platform, including billboards, television, offline and online media, online advertisement (mostly on Facebook and Youtube).

The latter is a clear example of how election content can be spread around without any meaningful fact-checking or moderation from these platforms. This video, for example was posted on 11 March, three weeks before the election and almost 1,7 million people watched it. The vast majority of viewers (97,5%) watched it on Fidesz’s Facebook page and only about 2,5% watched it through shared post. The high number of views and reactions are therefore the result of advertisement, rather than organic spread. According to the Facebook Ad Library, this post was advertised three times simultaneously (on Facebook and Instagram) between 11 March and 2 April, with different demographics targeted. We only see that over a million Ft was spent on each of them, but the exact figure is not disclosed by Facebook unfortunately.

Facebook video by Fidesz, containing disinformation narratives about the opposition; Source: Crowdtangle

Another example was when a similar message was shared by pro-government influencer Philip Rákay on Facebook, on 29 March, just before the election. The 3-minute-long video aimed to mobilize Fidesz voters a few days ahead of the elections summarized several pro-government disinformation narratives, including: “the Left is controlled and funded by a globalist international network aiming to displace Orbán”; “Márki-Zay is just a puppet of Ferenc Gyurcsány”, “the Left would destroy the utility cost cuts and support for families”; “they would open our borders for illegal migrants”. The video was seen by 374 thousand people, but reached over a million – according to Facebook Ad Library – thanks to the advertisement behind the video. Two ads were placed with the same video, with over a million Ft spent on both of them by Megafon Center. Megafon Center – as mentioned before - was established by pro-government figures ahead of the election to spread the messages of Fidesz with possibly taxpayer money.

Facebook video made by pro-government influencer Philip Rákay with several disinformation narratives about the opposition; Source: Crowdtangle

These examples show how disinformation narratives can be spread virtually unrestricted via videos on Facebook and Instagram, regardless of Meta’s efforts to curb disinformation on its platforms. Of course, it has to be mentioned that fact-checking Hungarian-language videos require significant resources, but its clear that Meta is not making enough effort in non-English language countries. These platforms systematically allow electoral disinformation to be spread and even advertised by official and gray-zone organizations. Although we can finally gather some evidence with tools such as CrowdTangle or Facebook Ad Library, but the depth of the information available on these sites are still restricted by Meta. Without the intervention of tech companies or state institutions, electoral disinformation could spread without any meaningful checks during the Hungarian elections.

Policy recommendations

The disinformation narratives spread by the governing party and the far right have undeniably become a dominant presence in the 2022 Hungarian election campaign. Fidesz took maximum advantage of its media dominance to spread false and misleading allegations and narratives about its political opponents, with virtually no external control. Fidesz's information offensive has further worsened the already disinformation-ridden Hungarian media space, putting even more pressure on the remaining independent press.

In the context of the disinformation narratives presented in our study, we can say that their spread had a significant impact on the election results, and social media played a key role in this. Political messages spreading in the gray zone and in the comment section reach their target groups almost completely unsupervised and the advertising system clearly favors the more well-resourced force.

There are many problems in modern political campaigning that could be addressed by active public engagement and stronger, but more thoughtful, regulation of social media. As we have pointed out in a previous study, the most obvious way to do this would be to create a package of legislation at the EU level (and, later, possibly in cooperation with democratic allies), as no single country is able to regulate these platforms effectively. This is essentially what the EU is already doing in the form of the Digital Services Act (DSA). Since the DSA is yet to be finalized, and regulators want to give companies time to adapt before it comes to force, meaning the DSA would be first applied in 2024 at the earliest.

Given that in Hungary the inaction of the state authorities has given the ruling party free rein to spread disinformation messages about the war, and an applicable EU regulation is year ahead, the task of combating fake news falls to the independent media and the civil sector. Support for civil initiatives to combat disinformation is therefore essential in the coming years. In the light of this, we make the following policy proposals:

- Supporting social action against the spread of disinformation. Since in Hungary no meaningful action can be expected from state authorities to combat the spread of disinformation, it is worth turning to society. In many Eastern European countries, for example, civil initiatives have been launched to curb online trolling. It would be worthwhile to support similar civic organizations through training, recruitment and networking.

- More should be spent on fact-checking, moderating content that is dangerous to national security or potentially violent. This is a manpower-intensive activity: Facebook's fact-checking activities in Hungary and Slovakia, for example, are carried out by one-man editorial teams - clearly inadequate, even if some people seem to be doing a good job. Policymakers can encourage technology companies to build up their fact-checking capacity in order to avoid further state interference. In addition, independent media initiatives that aim to fact-check political messages, should be more strongly supported. Even if they cannot provide a counterweight to the overwhelming resources of the state, they could at least offer an alternative to those who remain interested in quality and fact-based journalism.

- The European Union could adopt a non-binding recommendation on the operation of public service media, laying down the foundations for balanced reporting. Compliance with this could also be monitored annually by EU bodies, so that we could have an annual overview of the state of the media. This is particularly important if the EU wishes to maintain sanctions against Sputnik and RT, as the Hungarian example shows that the banning of Russian state media can be easily circumvented in practice.

- Reducing psychological harm: More intensive public discourse and targeted education are needed on the negative psychological effects of social media on individuals and communities, so that users can make educated choices about how much and for what purpose they use these platforms. In addition to the public sector, the civil sector can do much to raise awareness: inform, educate, and encourage caution, both in the general use of social media and in critical thinking.

- Enforcing the transparency of social media platforms is key: making the operation of content regulation, algorithms, and targeted advertising transparent would make companies' decisions and actions more accountable. If the DSA is done right, in the future researchers, journalists and civil society could have access to the platforms' databases through appropriate procedures to comprehensively study the processes in digital space and develop suitable responses to the challenges. The election campaign in Hungary is another proof that we need to support these efforts since social media platforms were not able to fully comply with their own rules and take down malign or inauthentic content.

- Reform of the content regulation systems of social media sites should be undertaken in a way that respects freedom of expression. Decisions on content regulation should not be automated but, as far as possible, be made by a real human being – even if assisted by algorithms. The starting point, however, is that the judgement of human activity should be undertaken by humans, not AI; any deviation from this should be carefully justified. This does not mean that everything should be done by humans, but that there should be meaningful human control over decision-making.

Political Capital in cooperation with GLOBSEC investigated the disinformation and anti-democratic narratives circulating in Hungarian media in the two months leading up to the 3 April 2022 elections. The research aimed to map the disinformation used in the election campaign and the actors involved in its dissemination, and to document the strategies used in the campaign.

[1] These allegations are factually incorrect - Ukraine has disarmed its arsenal as stipulated in the Budapest Memorandum

[2] Ukraine is in fact a sovereign state that determines its own foreign policy orientation. The Ukrainian people did not oust the Yanukovych regime in 2014 because of Western pressure, but because the President did not sign the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement at the last minute, presumably under Russian pressure.

[3] But Ukraine does not in fact have nuclear weapons, nor has it developed any.

[1] Examples for:

Independent media outlets: Telex.hu, HVG, 24.hu, ATV

Pro-government media outlets: Origo, Mandiner, Index, Magyar Nemzet and other media outlets part of Mediaworks, or regional and local newspapers of Central European Press and Media Foundation’s (KESMA) conglomerate

[2] https://transparency.hu/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Kampanykod.pdf, https://net.jogtar.hu/jogszabaly?docid=98900033.tv

[3] Former PM Ferenc Gyurcsány is a highly controversial figure in Hungarian politics. He served as Prime Minister of Hungary from 2004 to 2009 and now he is the leader of the biggest opposition party Democratic Coalition (DK). His persona – in the public’s mind – is connected with scandals, political instability, economic downturn, and austerity measures. He is a usual scapegoat for pro-government and opposition politicians alike.

Kiemlet kép forrása: 444.hu